The tattoos on his hands told a story of devotion. The bullets from his gun told a tale of desperation. In a brutal winter of 1914, Charles Hopkins was making headlines as the “Tattooed Bandit,” and though his bold ink told a tale of love, his actions would paint a portrait of a cold-blooded killer. After eluding the law in Seattle, his brazen streak of violence and strategic evasion to capture and discovery made him the most wanted man in the state. This is the story of a harrowing manhunt and a chilling clash between romance and rage that would forever be etched in the dossier of Snohomish County’s true crime history.

A Sailor’s Past and a Life of Crime

Born in England in 1888, Charles Hopkins began a life of wandering and defiance at the tender age of nine, running away to sea. It was on these waters that he etched his first story onto his skin. He fell deeply in love with the ship captain’s daughter, and to immortalize this affection, he had “TRUE LOVE” tattooed across his knuckles. On his right arm, a portrait of her was entwined with vines and flowers, a permanent declaration of devotion that stood in stark contrast to the life he would soon lead.

After a few years, Hopkins abandoned the sea for the United States, finding work as a boilermaker in Wisconsin. However, when the company went bankrupt, he began a transient life, eventually making his way to Washington. His criminal career began in earnest in 1909 with a burglary conviction in Ellensburg, which landed him a 14-year sentence at the Washington State Penitentiary. After serving four years, he was pardoned and sought a new start in Victoria, British Columbia, but his old habits followed him. He was arrested for illegal entry and carrying concealed weapons, and after giving Canadian immigration officers the slip, he returned to Seattle on February 2, 1914.

The First Murders and a Flight to Freedom

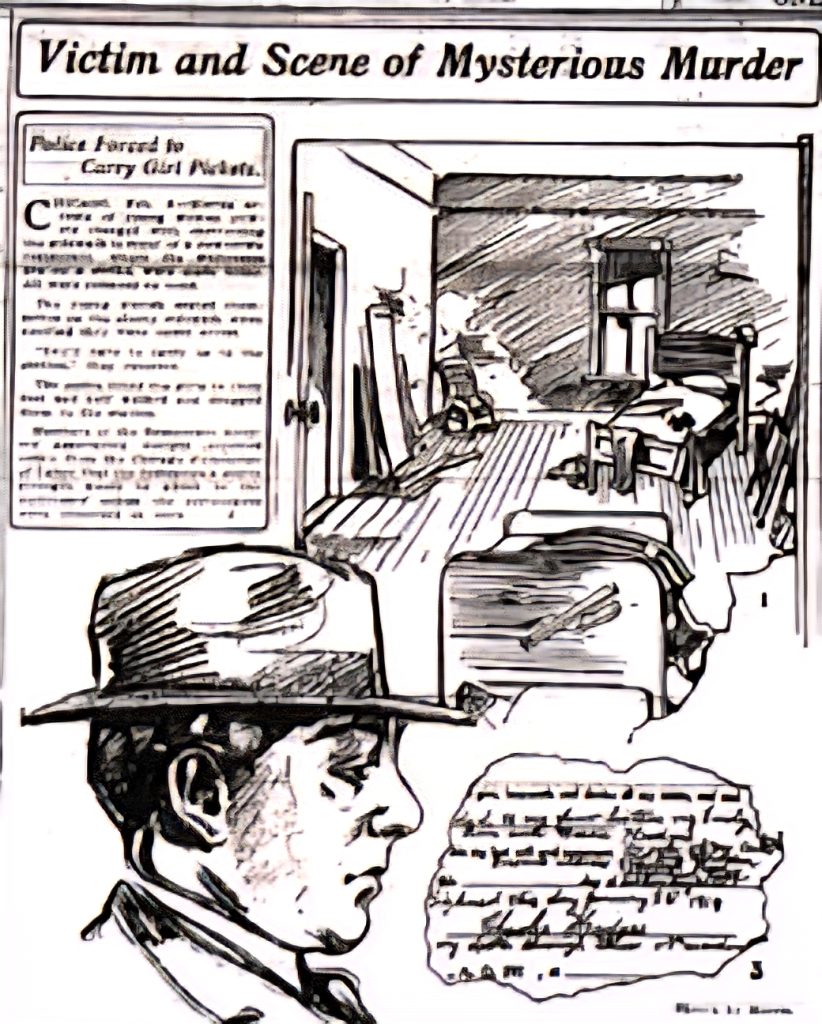

Just four days after arriving in Seattle, Hopkins’s story turned bloody. On February 6, 1914, police found a man named Charles Hodges brutally beaten and left for dead in a hotel room. Only 28 years old, he had been robbed and beaten with a heavy wooden bed slat, fracturing his skull. He died later that day, his killer $20 richer. The only clue: Hodges had been seen with a man with “TRUE LOVE” tattooed on his hands. It didn’t take detectives long to connect the distinct tattoos to Charles Hopkins. But by the time police put out a dragnet, the Tattooed Bandit had already vanished.

His freedom was short-lived, however. A month later, on March 26, Hopkins and an accomplice, Paul Putnam, were arrested for suspicious behavior and loitering on Grand Avenue in Everett. As a Patrolman, Lee Williamson attempted to call for a patrol wagon, Hopkins’s desperation boiled over. He snatched the officer’s service revolver and, in the ensuing struggle, shot and wounded the patrolman along with two civilians who tried to assist him. Hopkins escaped into the early morning gloom, leaving three men bleeding and Putnam to face a lesser charge after a willful surrender to police. The brutal escape cemented his status as a cold-blooded killer and fueled the already intense search.

The Manhunt and McMurray’s Bloody Chapter

Hopkins disappeared into the rugged landscape of the Pacific Northwest, with local newspapers and law enforcement agencies across Skagit and Whatcom counties tracking his every move. The search intensified, becoming the most extensive manhunt since the infamous pursuit of Harry Tracy, with a $500 reward for his capture, dead or alive. Yet, Hopkins continued to elude capture as his crime spree continued, first going on to rob the night watchman and a mill worker of their money and clothing in the early morning hours of March 27 at the Charles A. Blackman Sawmill in North Everett before disappearing again. He was a ghost in the vast forests, a figure of menace for every town from Everett to the Canadian border.

The search turned deadly again on March 28 near the small town of McMurray. Hopkins waylaid three loggers, Antone Olson, Tony Greb, and John Freeman, at gunpoint. After forcing them to cross a logjam over Ehrlich Creek at gunpoint and marching them into the trees, he clubbed them unconscious with the butt of his gun. When he searched them for money and only found a measly 45 cents, he mercilessly shot them several times before dragging their inert bodies into a nearby marsh.

Miraculously, Freeman regained consciousness the next morning and somehow managed to crawl across the logjam and a quarter-mile up the railroad tracks to a shack near Ehrlich Station to get help. As the alarm rang throughout McMurray, City Marshal Walter Hinman found Olson’s body hidden behind a long, but there was no sign of Greb. Based on Freeman’s description of their attacker’s distinctive tattoos, authorities were able to easily identify Hopkins as the culprit of yet another heinous crime.

Across Skagit and Whatcom counties, posses were mobilized in search of a cold-blooded killer while over 200 armed deputies guarded the railroad tracks, train stations, roads, and trails from McMurray to the Canadian border. Hopkins’s mugshot and identifying details were distributed to the press and forwarded to every nearby town, construction crew, and logging camp. Despite extensive searches around Ehrlich Creek for Greb’s remains, the only evidence recovered was two blood-stained pieces of black rubber – the broken grips from Hopkins’s revolver.

Capture, Trial and a Killer’s Defiance

During the next ensuing days on the run, Hopkins would survive by hiding out at various farmhouses along his journey, holding households at gunpoint and demanding hot meals. His reign of terror wouldn’t end until March 31, 1914, in a rooming house in Van Horn, Skagit County. It was late Monday evening when Hopkins happened to stop by Frank Yeager’s farm, asking for food and lodging. Having recognized the wanted man from newspaper descriptions of the tattooed bandit, Yeager volunteered to take Hopkins to the general store and rooming house, where he was rented a room upstairs by the proprietor, Clark Ely.

From there, Yeager went to fetch City Marshal Joseph E.Glover at Concrete, while Ely stood watch over Hopkins. Glover quickly organized a large posse that quietly had the building surrounded by 1:30 a.m. The marshal entered the room using a passkey and managed to handcuff Hopkins swiftly as he lay sleeping. Found in his possession were four handguns, including the .38-caliber revolver with the broken grips and ammunition with scored bullets, a trademark of the Tattooed Bandit. Fearing a lynch mob, officials transported Hopkins to Mount Vernon under heavy guard, where he was met not with violence, but with public curiosity as scores of people gathered in Concrete and Mount Vernon to see the man who had been making newspaper headlines as the “Tattooed Bandit,” the “True Love Bandit,” and even the “second Harry Tracy” because of the ruthlessness in which he killed.

The trial for the murder of Antone Olson began on June 12, 1914, with the local press giving the case so much attention that it took two days to seat an impartial jury. Despite his defense attorney’s creative argument, the prosecution had John Freeman as a key eyewitness and physical evidence linking Hopkins to the crime. After just 26 minutes of deliberation, the jury found him guilty of first-degree murder. As he was led from the courtroom, the man with “TRUE LOVE” tattooed on his hands uttered a chilling threat to the prosecutor: “I’ll get you for this.”

In an ironic twist of fate, Hopkins was sentenced to life in prison, as the death penalty had just been abolished the year before in Washington. He was transported to the state penitentiary in Walla Walla, where he would remain until his death on March 6, 1948, at the age of 60, never confessing to his crimes and famously declaring that society had made him a criminal.