In an era defined by towering timber and the relentless pursuit of new beginnings, the Pacific Northwest was a land of immense trees and even grander dreams. On the Lennstrom farm in Edgecomb, Washington, that dream took root in an unlikely place, in a stump. Crafted by hand and carved from the fused trunks of two ancient cedars, the stump house emerged as a fully livable space, complete with furniture, warmth, and a story that would outlast the very forest it came from.

A Shelter Born of Necessity

When thousands of settlers ventured into the Pacific Northwest during the 1800s, they faced a formidable landscape dominated by dense, old-growth forests. Building conventional homes was a monumental task, requiring immense resources and time. In a remarkable display of ingenuity, many pioneers found temporary, yet brilliant, solutions in the colossal tree stumps left behind by logging companies. These gigantic remnants, still rooted in the ground, offered an immediate opportunity for shelter while the arduous work of clearing land for farming progressed.

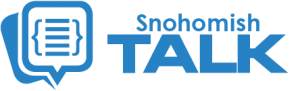

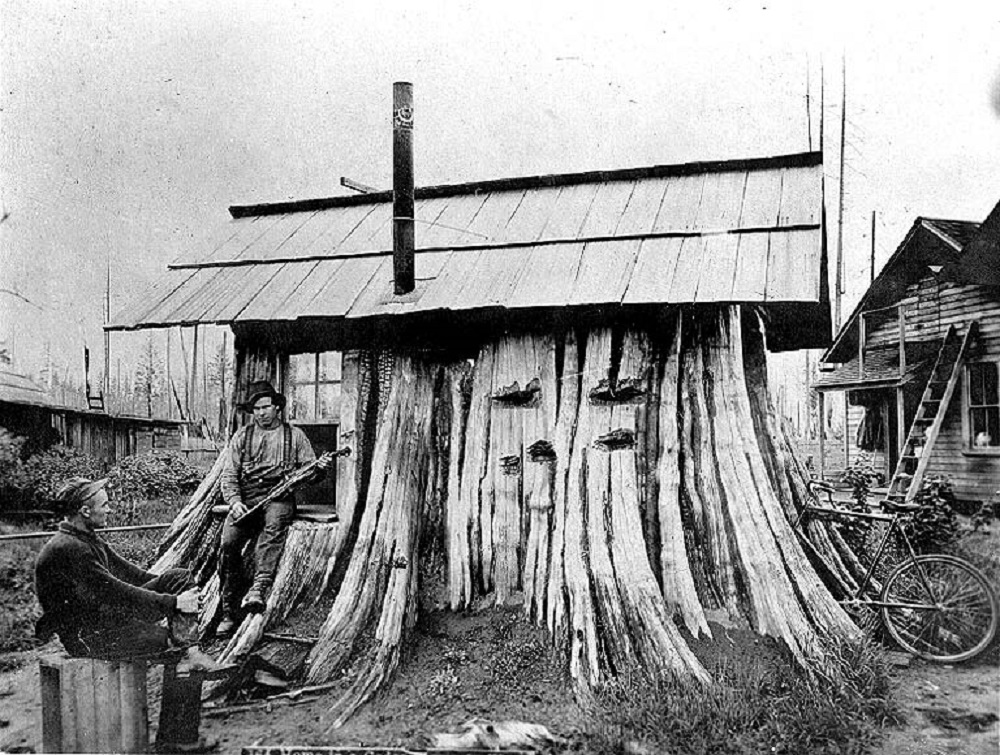

Transforming these natural behemoths into livable dwellings was no small feat. Not every stump was suitable, as many were too damaged or burned. But for those that were, the process involved meticulously hollowing out the interior to create thick, insulating walls. Pioneers then painstakingly crafted and installed solid roofs, cut openings for doors and windows, and even added stovepipes to provide warmth against the region’s notoriously cold and wet winters. Some of these remarkable stump houses even boasted two or three stories, fully equipped with spaces for cooking, sleeping, and storage, serving as complete family homes until more conventional structures could be built.

Though perhaps not “perfect” in the traditional sense, these whimsical abodes, appearing as if magically created by forest elves themselves, were a testament to the settlers’ creativity and resilience. After families moved into their permanent homes, these trusty stump dwellings were often repurposed, sometimes housing livestock, extending their useful life on the frontier.

The Making of a Marvel: The Lennstroms’ Cedar Creation

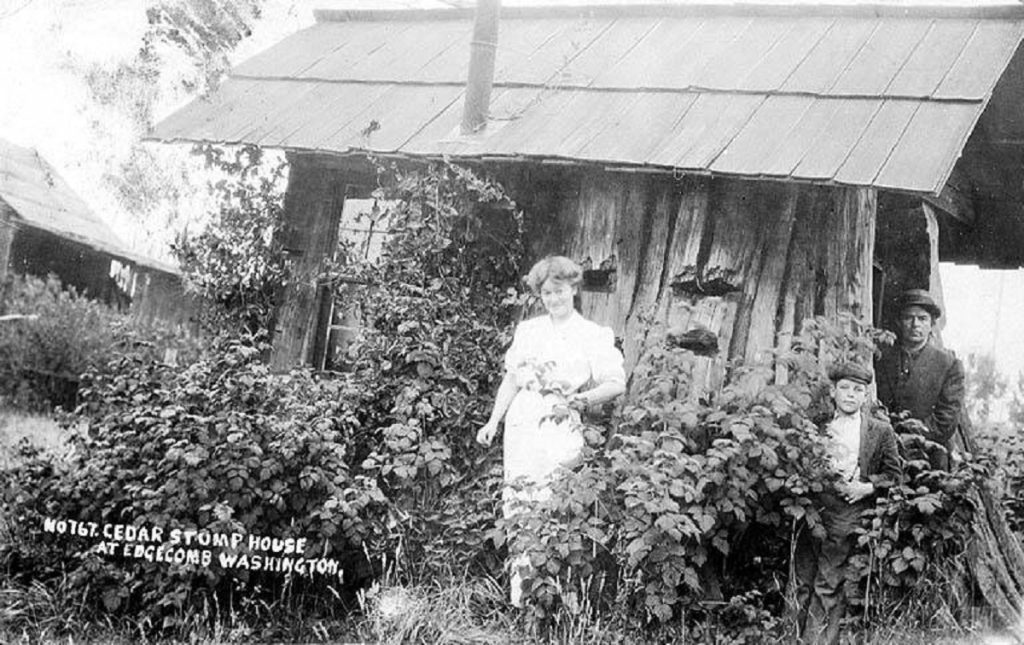

Of all the stump houses built during this period, none captured the public imagination quite like the one on the Lennstrom family’s dairy farm in Edgecomb, Washington. Swedish immigrants Gustav Erik Lennstrom and his wife, Brita Charlotta, along with their three children, had settled on a farm located along 172nd Street NE, just east of what is now the Arlington Airport. Around 1900, they felled two massive cedar trees that had grown together on their new property for wood, leaving behind a single, sprawling stump. When Brita’s brother, Johan Axel Westerlund, a skilled cabinet-maker from Sweden, joined the family, he found a new purpose for the colossal remnant.

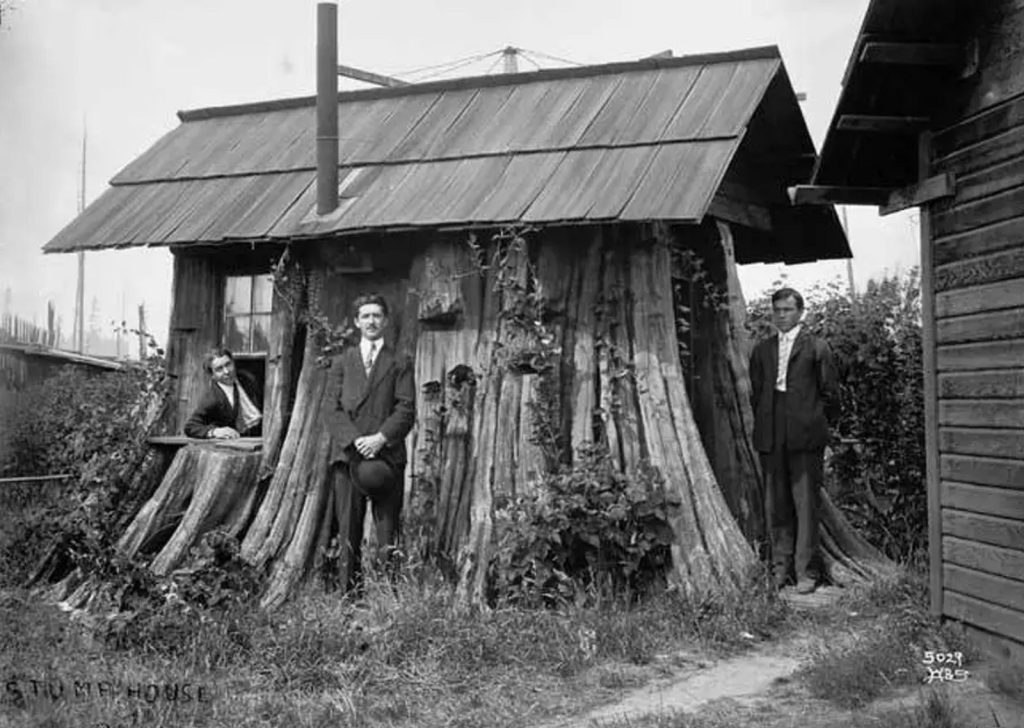

Using his woodcrafting skills, Westerlund meticulously hollowed out the 22-foot-diameter stump, while Gustav finished the house by placing a door, window, and roof on it. The family also installed a wood stove inside the stump to keep it warm during the cold days. The Lennstrom family, consisting of three adults and three children, used the stump house as their temporary home, relying on its thick walls to provide insulation from the elements. After several months, they were able to build a more conventional home on the property. However, Johan Westerlund reportedly continued to live in the stump house because he liked it so much.

The Snohomish Stump House Goes “Viral” in the Early 20th Century

The Lennstrom stump house quickly became a great curiosity and a regional icon. Its unique blend of human ingenuity and natural wonder captivated people far and wide. This fame was primarily thanks to photographer Darius Kinsey, who in 1901 immortalized the home in a series of eight stunning photographs that would make the stump house a viral sensation for its time. For the next two decades, he actively marketed these images as postcards and stereoview cards, and even used a tiny rendering of the stump house on his business stationery in 1902.

The house appeared on no fewer than 38 different postcards and even on souvenir china, according to research by Joni Sein, director of the Edmonds Historical Museum, which once featured an exhibit on stump houses. The fame, however, came with some amusing inaccuracies when some postcards erroneously identified the home as being in Seattle, Everett, or even Oregon, highlighting its widespread appeal beyond its actual Edgecomb setting. Sein also noted that many of the photos showing the whole family gathered around the stump were most likely staged, a common practice at the time to portray a wholesome, pioneering spirit.

A Fiery Farewell Rooted Now in Memory

The stump house remained on the property well into the 1930s, weathering decades of Pacific Northwest storms and standing as a beloved landmark. Its fame endured, drawing visitors who had seen it on postcards or heard stories of its unusual charm. But as time passed, the structure began to show signs of wear. The farm changed ownership, and the new owners hoped to preserve the stump house by donating it to the city of Arlington. Newspapers briefly buzzed with the proposal – could Snohomish County’s most iconic pioneer oddity become a public park centerpiece?

The logistics proved insurmountable. Moving a 22-foot-wide, densely rooted cedar stump weighing multiple tons required machinery and funds far beyond the 1940s capabilities. After much debate, an attempt was finally made to move the stump house in 1946, but the effort ended in heartbreak as the structure was damaged beyond repair in the process. With no path for preservation left, the remaining remnants of the stump house received a fiery farewell.

Today, the story of the Lennstrom Stump House lives on in photographs, museum exhibits, and the memories of those who once stood in its shadow. It remains a rare historical oddity, showcasing the intersection of human resourcefulness and the rugged natural environment. And while the stump itself may be gone, its story continues to inspire while rooted deeply in the soil of Snohomish County’s past.