A brooding sky met a restless sea on a crisp November day in 1916. The air, thick with tension, hung heavy over Puget Sound’s crashing waves. Gray clouds carried an ominous sense of foreboding, seemingly foreshadowing the impending storm of violence that would descend upon the docks of Everett. A burgeoning industrial hub, the rapidly growing city was about to become the stage for one of the bloodiest labor conflicts in American history.

In the distance, the waters of Port Gardner Bay churned under the weight of two approaching steamships, the Verona and Calista. Together, they carried something far heavier than any lumber, as onboard these vessels was the fierce determination and unwavering support of hundreds of Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), better known as Wobblies, as they stood steadfast in solidarity with the local shingle weavers embroiled in a bitter labor dispute, ready to fight whatever the cost may be.

On the docks, a tense assembly of local law enforcement and citizen vigilantes remained on guard, heavily armed and fueled by rumors that painted the Wobblies as a dangerous horde of anarchists threatening the safety of their town. The air crackled with a mix of fear and defiance, each side poised on the brink of confrontation.

Then, a single shot shattered the fragile peace. A chaotic eruption of violence followed, forever staining the waters of Port Gardner red. The Everett Massacre, as it came to be known, was a pivotal moment in Pacific Northwest history, leaving a legacy that continues to resonate within the community. Its impact wasn’t confined to a single bloody day but reverberated through labor relations, political discourse, and the city’s very identity.

Everett: A Union Town Built on Industry

Once proud to call itself the “City of Smokestacks,” Everett was built as an industrial powerhouse heavily funded by East Coast investments. The city’s early industries included a paper mill, a nail factory, a whaleback bargeworks, a smelter, an ironworks, and numerous lumber and shingle mills. By 1910, the Everett waterfront boasted shipbuilders, a cannery, a flour mill, and two iron works, with the lumber and shingle trade becoming the backbone of its economy. Prominent businessmen like David Clough, Roland Hartley, Fred Baker, and Joe Irving, along with banker William Butler and the influential Commercial Club, held significant power in the town.

From its inception, Everett was also a union stronghold. Trade unions formed almost as soon as the city began, and while most of these languished in the Panic of 1893, union strength surged by 1900 as the country gained newfound prosperity. The city directory of 1904 listed numerous trade unions, reflecting the diverse and growing labor movement. With the arrival of a large immigrant population in the early 20th century, some advocating conservative socialism, union membership flourished, making Everett one of the strongest union towns in the Pacific Northwest. The Labor Journal began publication in 1909, and the city even supported a Socialist Party weekly newspaper, The Commonwealth, from 1911 to 1914.

The Strife of Everett’s Shingle Weavers

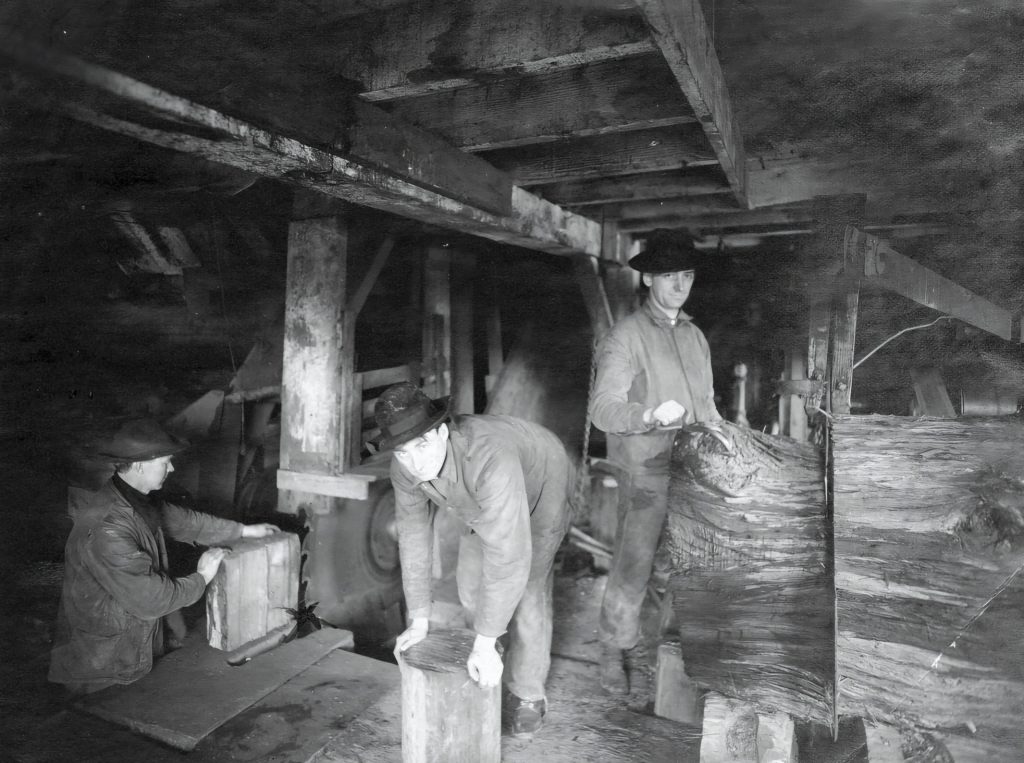

As Everett’s industrial might grew, so did its reputation as a significant exporter of red-cedar shingles. At the heart of this booming industry were the shingle weavers, whose skill and dexterity earned them their distinctive title. The term “shingle weaver” originally referred to those who stacked and bundled shingles with the precision of a skilled artisan, but it soon encompassed all shingle mill workers, including sawers, filers, and packers.

In 1910, shingle weavers considered themselves well-compensated at $4.50 a day, starkly contrasting the $2.25 earned by logging camp workers. However, this higher wage came at a steep price. Shingle mills were perilous places, where ten-hour shifts were the norm and safety was an afterthought. The machinery, designed for efficiency rather than protection, featured unshielded saws that whirred through the dark, damp interiors of the mills. Accidents were so frequent that missing fingers became a grim badge of the trade, and the ever-present cedar dust led to “cedar asthma,” a debilitating condition that slowly choked the life out of many workers.

Some even lost their lives in catastrophic and ultimately preventable industrial accidents. Not to mention, the industry itself was a cruel mistress, with the shingle economy operating in boom and bust cycles with wages consistently unsteady. For these reasons, much of the city’s male workforce was unionized by the early 1900s.

United We Stand as the Wobblies: The Formation of the Industrial Workers of the World

Around this time, a radical union known as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) emerged in 1905 in Chicago with a bold vision of uniting workers into “One Big Union.” Unlike the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which focused on skilled workers and maintained separate craft unions within the same plant, the IWW sought to bring together workers across all trades, classes, genders, and even national borders. This inclusive approach aimed to harness greater collective strength and solidarity among the working class.

The Wobblies, as IWW members were called, began organizing miners, lumberjacks, and shingle workers in the Pacific Northwest. Their efforts were particularly successful in the logging camps, where they recruited a significant number of members. Buoyed by their success in the forests, IWW organizers turned their attention to urban laborers, striving to extend their influence into the cities. However, like the individual trade unions, the strength of the IWW fluctuated with the economic tides.

Waves of Change: Spokane’s Influence on Everett’s Labor Movement

Still, the IWW’s influence spread across the Pacific Northwest, with their activities beginning to draw significant attention and resistance. So much so that on New Year’s Day 1909, a Spokane ordinance prohibiting street meetings came into effect, primarily targeting IWW street speakers who had arrived the previous year to challenge exploitative employment practices.

Wobbly organizers continued their public speaking through the summer, albeit within the constraints of the ordinance. Meanwhile, Salvation Army evangelists enjoyed more leniency for their public proselytizing, prompting the Wobblies to challenge the city for violating their free speech rights. They called on their membership nationwide to converge on Spokane and test the ordinance, leading to overflowing jails filled with IWW protesters, with more arriving daily. The Wobblies’ passive-resistance tactics in Spokane proved so effective that on March 9, 1910, the Spokane City Council unanimously voted to repeal the ordinance.

Everett citizens observed the Spokane situation from a distance, while industrialists and mill owners watched with growing apprehension. Everett workers contributed funds to support the Spokane cause, and Wobbly speakers appeared in Everett alongside the Salvation Army at various locations on Hewitt Avenue.

The IWW found a cause in Everett in 1912 when a group of temporary, non-union workers took jobs with the Great Northern Railway to clear a mudslide from its tracks. When these workers were paid, they could not cash their checks in town. The Wobblies’ support for these workers spurred the City of Everett to pass Ordinance No. 1501 on February 18, 1913, imposing restrictions on speaking locations along Hewitt Avenue. Despite this, IWW speakers continued their efforts, setting up their soapboxes in compliance with the ordinance.

The Events Leading Up to the 1916 Everett Massacre

Tensions only heightened as the once thriving lumber economy, which had soared in 1912, plunged into a deep economic depression from 1914 to 1915. With its collapse, shingle-weavers’ pay decreased, forcing many to take non-union jobs and even seek jail for room and board as they struggled to survive.

In January 1916, with shake prices rising, labor leader Ernest Marsh saw an opportunity to revive the Brotherhood of International Shingle Weavers of America. Marsh, executive secretary of the Everett Shingle Weavers Union and the Labor Journal newspaper editor since 1909, aimed to transform the union into a more inclusive industrial union that would unite all shingle-mill employees.

With a target date of May 1, the shingle-weavers union demanded a return to the 1914 wage scale. While companies throughout the state complied, Everett’s mill owners remained defiant, refusing to even meet with union representatives. On May 1, 1916, Everett’s shingle weavers went on strike, with Marsh heading the strike committee, setting the stage for a significant labor conflict.

The IWW, which also faced hardships during the economic downturn, sought to rebuild its membership by supporting the Everett shingle-weavers’ strike. They brought in one of their most persuasive speakers, James Rowan, to address the Everett community on July 31, 1916. Rowan drew a large crowd of spectators,

Snohomish County Sheriff Donald McRae, a former shingle weaver, was initially sympathetic to labor unions. However, as a resident of the logging town of Marysville, he grew increasingly concerned about the IWW’s radical ideology and potential threat to the community’s stability. Everett’s mill bosses increasingly relied on him to help rid the county of the troublesome Wobblies.

At the July 31 rally, McRae arrested IWW organizer Rowan, sending a clear message that he would not tolerate the Wobblies’ activities. Despite the arrest, Rowan returned to his soapbox only to be carted off once more, this time to the city jail, and rereleased, after which he returned to Seattle.

Encouraged by the absence of violence, the Seattle Wobbly office sent Levi Remick to establish an IWW office in Everett. His office distributed the Industrial Worker newspaper, covering the shingle-weavers’ strike.

Tensions only escalated thanks to events on August 19, 1916, when mill owner Neil Jamison brought in strike breakers who attacked the strikers. The shingle-weavers’ union blamed Sheriff McRae for not preventing the violence.

In response, the Wobblies sent their best speaker, James P. Thompson, to Everett. On August 22, 1916, Thompson spoke in support of the shingle weavers but was arrested by Sheriff McRae, along with other Wobbly speakers.

Despite these arrests, the Wobblies’ Everett office continued to operate, further angering Jamison, who, on August 29, led a defiant march of strikebreakers to the Everett Theater. As repression increased, many trades unionists and Everett citizens began supporting the Wobblies’ right to free speech and protested the sheriff’s violent tactics. In September 1916, Everett passed Ordinance No. 1746 to further restrict street speaking, signaling the authorities’ determination to suppress the Wobblies.

The Beverley Park Incident Preludes the Bloodshed of the Everett Massacre

The Wobblies, however, would not go quietly. On October 30, 1916, a group of Wobblies arrived in Everett by boat, intending to hold a public meeting. Sheriff McRae’s deputies, armed with rifles, met them at the dock and ordered them to speak in a less central location. When the Wobblies refused, a confrontation ensued, resulting in several IWW members being beaten.

Deputies then took the Wobblies by force, loading them into trucks, where they were then driven to a secluded, wooded area near the Beverly Park interurban station southeast of town. In the darkness of cold rain, McRae’s men formed a gauntlet of violence, as one by one, the men were beaten with clubs, guns, and rubber hoses. A nearby family, disturbed by the sounds of the assault, witnessed the brutal scene. The injured Wobblies were left to fend for themselves, making their way back to Seattle as best they could.

The news of the Wobblies’ brutal treatment sparked outrage among Everett residents. Despite the heavy rain, an investigation committee, including prominent figures like Reverend Oscar McGill and labor leaders, uncovered evidence of the violence. In a report, labor leader Ernest Marsh condemned the “inhuman method of punishment.” The events at Beverly Park deepened the divide between the authorities and the IWW, leaving a lasting mark on the city.

The Fight for Workers’ Rights: A Very Bloody Sunday on the Docks of Everett

On November 5, 1916, approximately 300 Wobblies departed Seattle aboard the steamers Verona and Calista, bound for Everett. They intended to hold a public demonstration at the corner of Hewitt and Wetmore avenues that afternoon. Rumors had spread that the Wobblies intended to set fire to Everett. Sheriff McRae’s deputies, numbering around 200, assembled at the city dock to prevent their landing. As the Verona approached, McRae demanded to know who was in charge. When the Wobblies responded that they were all leaders, he denied them permission to disembark.

Just then, a single shot rang out, followed by a chaotic exchange of gunfire that lasted ten minutes. Though the source of the initial shot remains unknown to this day, the majority of the ensuing gunfire would come from the vigilantes on the dock. Passengers on the Verona panicked and rushed to the ship’s opposite side, nearly causing it to capsize. Bullets struck the pilot’s house, forcing the captain to maneuver the boat away from the dock and return to Seattle. The Calista, seeing the chaos, decided not to attempt a landing.

Two deputies lay dying on the dock, with 20 others wounded, including Sheriff McRae. Official reports state five members of the Wobblies lost their lives in the massacre, with 27 wounded, but in reality, as many as 12 Wobblies probably lost their lives that day, their bodies later surreptitiously extracted from the waters of Port Gardner Bay when the area was free of witnesses.

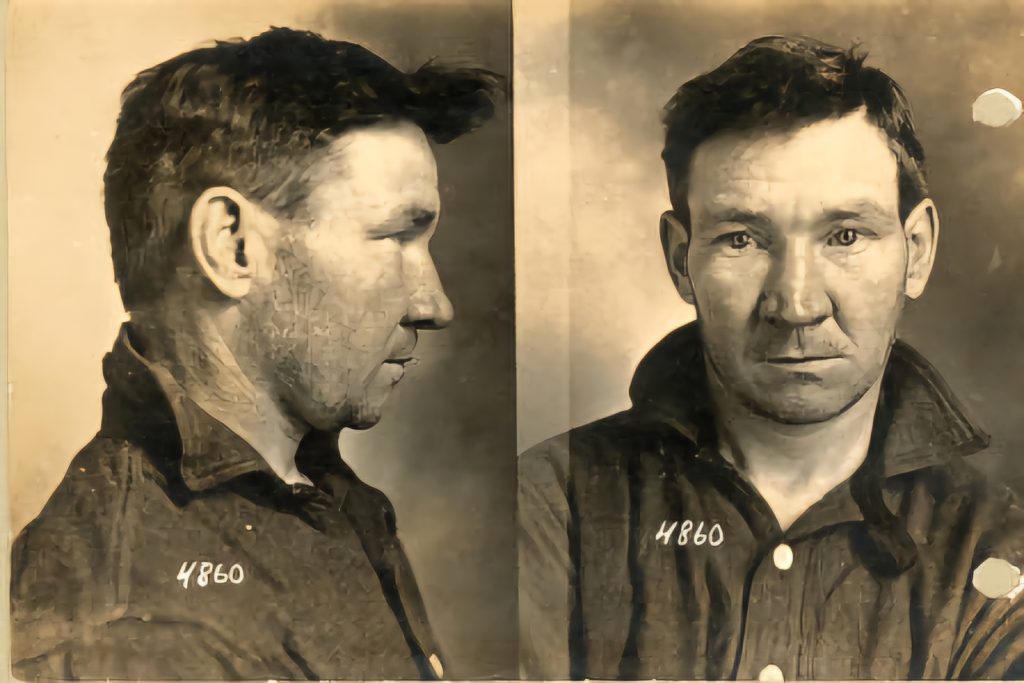

When the two vessels returned to Seattle’s docks, they were met with handcuffs as 74 Wobblies were arrested and brought back to the Snohomish Jail in Everett. National Guard troops were called in as fear gripped the town as armed deputies policed the streets in the wake of Wobblies’ trail.

First to be tried was fellow teamster and IWW leader Thomas Tracy, who was charged with the murder of one of the deputies. In the end, a Seattle jury would find him not guilty due to the possibility that the deputy may have been killed by friendly fire. Ultimately, due to the chaos of the Everett Massacre and the limitations of forensic science at the time, it was impossible to determine who fired any of the event’s fatal shots, leading to the release of all other Wobblies.

The Everett Massacre is a Poignant Reminder of the Cost of Industrial Progress and the Need for Labor Advocacy

The Everett Massacre is a poignant remembrance of the price paid for industrial progress and the enduring struggle for labor rights. The violent clash of November 5, 1916, underscored the extreme measures taken by both labor activists and authorities during a period of intense industrial conflict. The tragic loss of life and the subsequent legal battles highlighted the urgent need for better working conditions and the protection of workers’ rights.

The massacre served as a catalyst for change, drawing national attention to the plight of workers and the harsh realities of industrialization. It also exposed the deep-seated tensions between labor and management and the lengths to which authorities would go to suppress dissent. Thomas Tracy’s acquittal and the other Wobblies’ release demonstrated the complexities of justice in the face of such turmoil.

Today, the Everett Massacre is a moving reminder of the historical struggle for labor rights. It calls on us to reflect on the sacrifices made by those who fought for fair treatment and to recognize the ongoing need for advocacy in the face of industrial progress. As we remember the events on the docks of Everett, we are reminded of the cost of progress and the enduring importance of standing up for workers’ rights.